Episode 9: Factoring a Neighborhood

Why housing is ripe for a Tesla-like disruption, and the one weird trick that disruption will borrow from grade school math.

◄ |

![]() Home |

Listen |

Watch |

Design |

Map |

Join |

►

Home |

Listen |

Watch |

Design |

Map |

Join |

►

Transcript

Housing ripe for change

Intro [music]

Factoring in Design

How Factoring Works

How to Factor a Design

Step 1: Look for patterns

Step 2: Combine redundant elements.

Step 3: profit!

Case Study #1: 2sky

Case Study #2: SpaceX

Case Study #3: Tesla, Inc.

Let’s factor some real estate!

Step 1: Which elements repeat?

Step 2: Combine redundant elements

Step 3: Count your money!

Better Amenities

Better Economics

Safer and Healthier

How factoring reduces stress

Yeah, but will people buy it?

Close [music]

▲ Housing ripe for change

Have you ever gotten a little lost in a neighborhood where all of the houses look a little too much alike? Not just the houses; the yards and the streets. Everything.

I love those places. Not because they're great, but because they're miserable! Housing today is very much like the computer industry was in 1975: a little bit too much going on on the high end, not enough going on in the low end and completely ripe for new ideas and disruption.

What's different this time? Well, housing is 29.5 times bigger than the Internet. Add energy, transportation and food and, as I explained in Episode 8, you get something that's 77 times bigger than the Internet. It's the greatest business opportunity of all time.

In Episode 2, I talked about how, in order to end the mass extinction, which will inevitably include us, we need to use 20 times less land, resources and energy than we do now. That's a 95% reduction.

Are you skeptical? Well, that does sound like the worst kind of lifestyle diet. But that's the old way of thinking. In Episode five, I talked about how the whole point of design is to resolve false dichotomies. So right now, let's design a neighborhood that's many times better for the planet and many times better for people.

To accomplish that, all we'll need is a little trick you encountered in grade school.

▲ INTRO [music]

Cities designed like modern Edens, for economic and ecological abundance. I'm Kev Polk, your guide to Edenicity.

Welcome to Episode 9. By the time we reach the end, you'll understand the power of factoring in design. We'll explore its power in three case studies, then discover, through a worked example, how it can dramatically improve the performance of a small housing development—both for the developer and for the residents.

▲ Factoring in Design

In Episode 5, I made a series of observations on how to design for greatness. Observation # 4 was that design factors redundant elements. In other words, you can measure the quality of a design by how well it factors longstanding redundancies. I promised to go into detail in this episode.

Episodes 8 and 12 also provide examples of factoring a transportation system. Loop transit or even subways can move 250 times as many people five times faster while using 90 times less energy than your car. That already far surpasses the 20× improvement we're looking for. But can it be done in real estate?

Tesla Incorporated CEO Elon Musk has used factoring to disrupt the auto, aerospace and energy industries. As we'll discover in a moment, factoring is very popular in the software industry, where Musk launched his first two companies. But it's an essential tool to massively improve the performance of any industry, especially housing.

This is exciting news for several reasons:

- Residential real estate is a much bigger slice of the economy than the Internet.

- There's a housing shortage, and millennials are not happy with existing choices.

- A factored design tends to be much greener by dint of its efficiency. This is how higher profit margins can work hand in hand with smaller ecological footprints.

A growing number of projects has even increased land values and incomes by healing past environmental harms. I'll discuss those in future episodes.

▲ How Factoring Works

Let's start with how factoring works. You first encountered factoring in grade school math. It may have seemed like a strange game where you break apart numbers and put them back together again. Something like X×A + X×B = X×(A + B). In this expression, X is the common factor of X×A and X×B, so X can be factored out.

Your teacher may not have mentioned how useful this can be in the real world.

As a kind of a trivial example. Just imagine things like batteries, candy, toilet paper, beverages—things that are sold in packs of 2,3,4,5,6 and so on.

So imagine you go to a store and you buy six 4-packs and six 3-packs of something. Now how many do you have? You could just do to multiplications and add them up. 6×4 = 24. 6×3 = 18. Then you hold those numbers in your mind and add them. 18 + 24 = 42.

But it's actually easier to group the packs first and then do just one multiplication: 4 + 3 = 7. Then 6×7 = 42. Simple as that!

The second method is better because addition is easier than multiplication. Anything you can count, you can factor, including bricks and mortar. That's right. You can factor reality!

▲ How to Factor a Design

Here’s the recipe:

- Look for patterns

- Group repeated elements

- Profit!

Let’s take these steps in detail:

▲ Step 1: Look for patterns

Patterns are elements that repeat. So an element in math is a number or letter, and you'll find them in expressions like A×X + B×X + C×X. And as we just did with our packs of batteries (or what have you), we factored out that X.

Here's another example. Compute the running sum of A×B×X + C×D×X + E×F×X for 100 values of X and constants A, B, C, D E, F. And this is really a very typical thing that you run into in computing all the time.

▲ Step 2: Combine redundant elements.

Did you notice how, in each case, it's just the X that repeats? That's the common factor in each term of the expression. Once you've found the common factor, you can simplify the expression so that nothing repeats. The first expression now reads X×(A+B+C).

In the second example, typical of a loop of computer code, we can pre-compute G=(A×B+C×D+E×F) before the loop, then sum the 100 values of X, and then just multiply that by the constant G.

Now all the expressions are factored, meaning nothing repeats. Okay, what's next? Oh yeah...

▲ Step 3: profit!

This step involves taking stock of what factoring saves you. Let's start with the obvious application: software. Computers without specialized hardware can take a lot more time to multiply and calculate exponents than they do to simply add two numbers. So in the examples we just explored, software running the factored expressions above would save 2 multiplications in the first example, making it about 3 times faster, and 597 multiplications in the second example, making it about 200 times faster.

▲ Case Study #1: 2sky

All of which brings us to the first of our case studies. Long ago, I wrote an astronomy application for the Palm Pilot: that distant ancestor of the modern smartphone. My app, called 2sky, animated the sky in real time using three loops: one to retrieve star positions from a database, another that figured out where the Earth, Moon and planets and comets and asteroids were in their orbits, and a third loop that figured out what you could see from where you stood on the Earth. When I took off the shelf equations and factored them in each loop, its performance gains multiplied together with the other loops to give me this massive speed up—like 5×8×200 = 8,000 times faster!

Now, of course, I also used much subtler forms of factoring, for example, by pre- sorting my databases by position and brightness and many other techniques that are much too detailed to get into here. My factored design made the difference between award-winning software with thousands of ecstatic customers ... and something that would have been far too slow and clunky to sell it all.

Now, here's the kicker: I wrote 2Sky for devices 1,000× slower than even the dumbest of today's smartphones, with 1,000× less storage. Yet its still ran as smooth as today's smartphone astronomy apps. Some of them may even use bits of my code.

You're probably thinking something like, "Yeah, but that's software. Here in the real world—"

Actually, in the real world, factoring works exactly the same! Opportunities to factor abound, and it could blow the lid off your product's performance.

▲ Case Study #2: SpaceX

Rocket technology took a giant leap forward when SpaceX started 3D-printing major components of their engines. Now it's routine. Before they did this, rocket motors were made of many metal parts bolted or welded together in hundreds of places. Each bolt or weld was an opportunity for the rocket to break under heavy load, so they were reinforced, adding a lot of weight. Engines could have part counts in the hundreds to thousands. The 3D-printed Merlin 1D engine cut the part count way down, resulting in a thrust to weight ratio of 181.

That's astonishing because for decades the best ratio rockets could manage was about 77. What SpaceX did was like entering 100 meter dash, where the world record has stood above 9.58 seconds for decades, and running it in 4.08 seconds.

By the way, this design also dramatically reduces opportunities for manufacturing defects and the subsequent need for inspections, all of which paves the way toward lower cost and reusability. Reusable rockets factor out the expensive equipment that is usually discarded with each launch, which could ultimately reduce the cost of space access by two orders of magnitude.

▲ Case Study #3: Tesla, Inc.

An internal combustion engine has something like 2,000 moving parts, while Tesla's electric motor has about 20. Now, true, its typical battery pack has 7,000 cells, which would seem to be a problem. But these are like the transistors in your cell phone: mass produced with painstaking automation and quality control to minimize variation and therefore the chance of failure. They're designed to function as a single, reliable unit, much like your entire smartphone, or the car's built-in computers.

By the way, those computers allow the manufacturer to update the handling and other performance aspects of the cars via wireless software updates. Notice that these wireless updates factor out the millions of parts and service hours that would otherwise be involved in a physical recall or an upgrade.

By having 100× fewer moving parts and doing remote software updates, Tesla can affordably design, test, redesign and build cars that are much safer, faster, more reliable and more efficient than anything that came before.

Now notice how in product design, the numerical advantage of factoring improves quality in many areas at once. Also, notice how a Tesla doesn't look too different from cars already on the road.

Factoring can give a product incredible advantages without having to look weird. From the business end, this can actually be a problem. Without additional attention to decoration, heavily factored designs can look so normal that their humble appearance can mask their revolutionary performance.

Ready for our big payoff?

▲ Let’s factor some real estate!

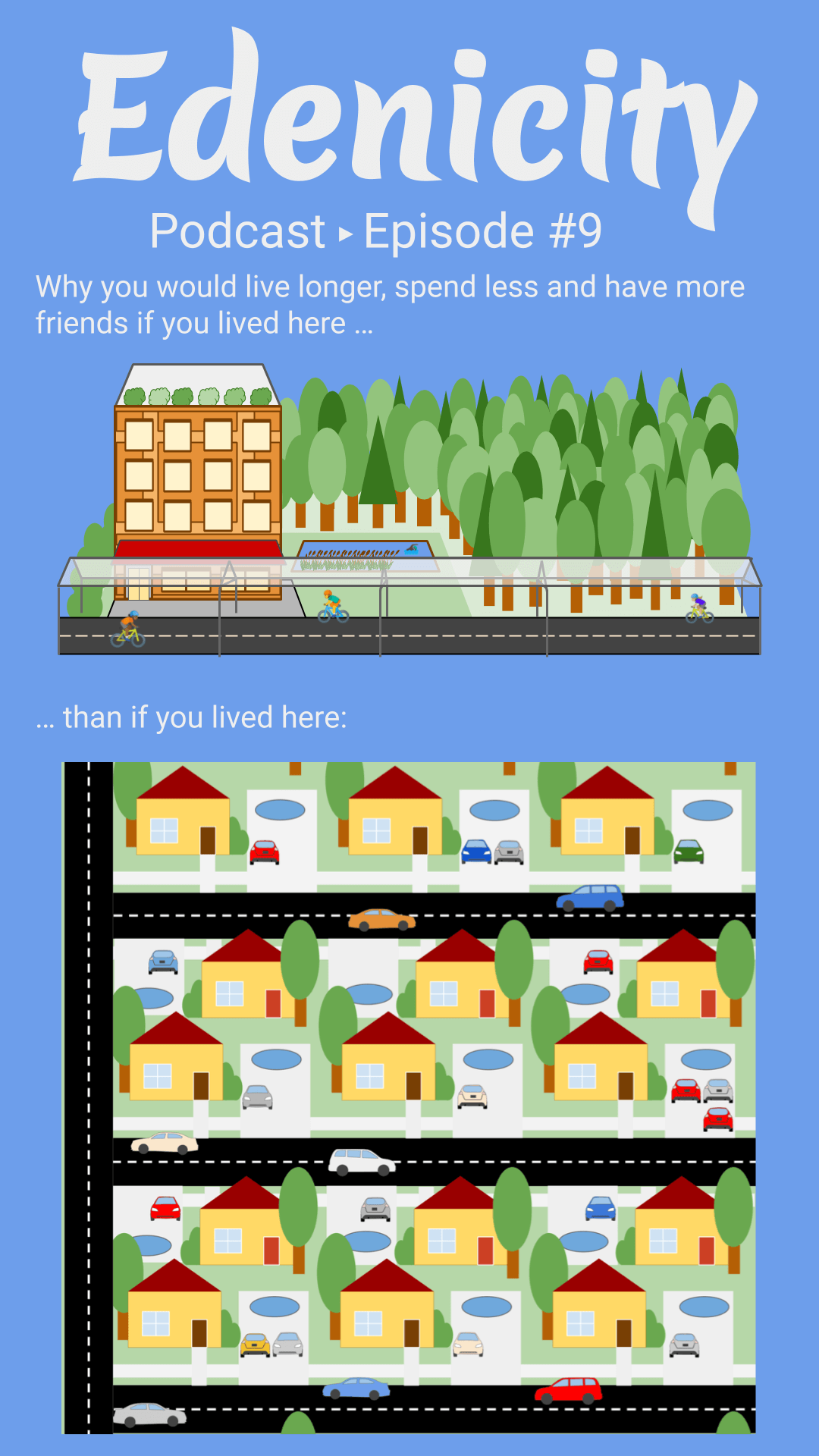

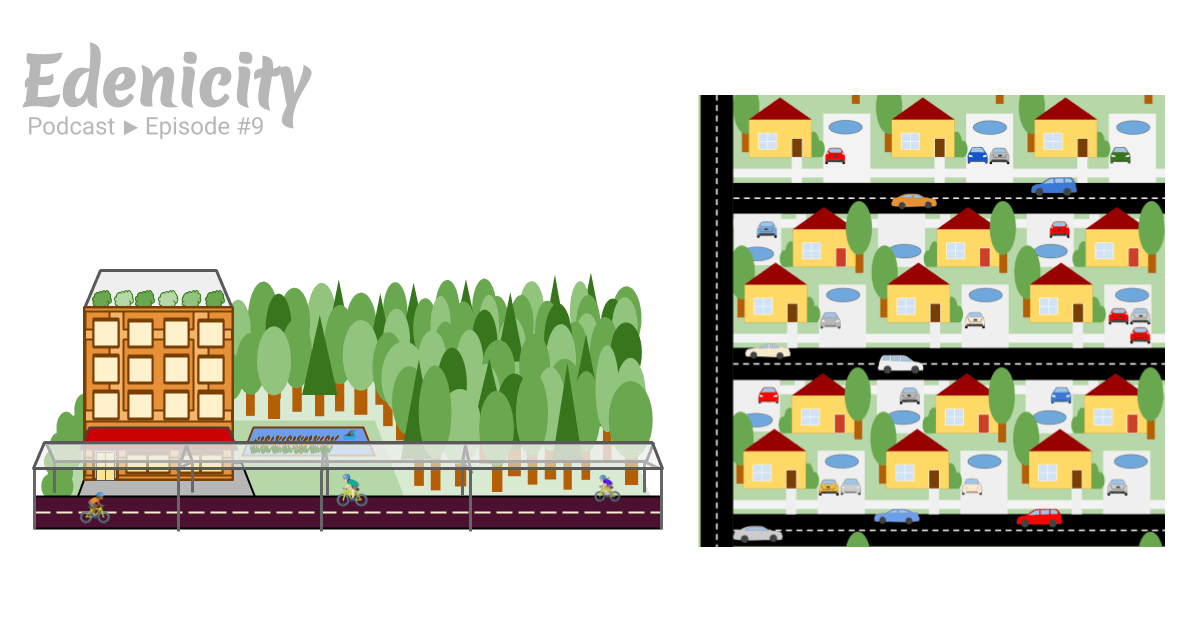

Think of that neighborhood I mentioned at the start of the program. I actually drew it in this episode's cover. Let's run it through that 3-step factoring process.

▲ Step 1: Which elements repeat?

Elements in this case mean physical structures. Notice that the cover design for this episode has:

- 15 houses (each with its own exterior roof and walls),

- 4 streets (26 feet wide),

- 20 cars and parking for them,

- 15 small swimming pools and

- assorted trees and plantings, including perhaps a few small vegetable gardens.

▲ Step 2: Combine redundant elements

Here's what I came up with for a factored design. It's actually the building you see in the foreground of the edenicity Season 1 cover art. This, in turn, is actually kind of an early outtake from the Reference Design that you can download at Edenicity.com.

Anyway, let's do the addition: One apartment building with 30 apartments, a gym and a cafe. One bike path. One big pool. One large wooded park planted with edibles such as fruit trees. One large rooftop greenhouse to grow fresh produce year round for the cafe. The rooftop greenhouse improves the building's climate control and factors the many small neighborhood food gardens, opening up new opportunities for the cafe.

Let's talk about that ground floor cafe. Mixing residential and commercial space like this is something you'll see in New Urbanism, which designs neighborhoods to meet most of your needs within walking distance.

Now, wonderful though New Urbanism is, it still bends over backward to accommodate the car and the detached home. That means dedicating amounts of space to parking and roadways that seem absurd next to a factored design.

With efficient bike access, it's possible to fill the transportation gaps economically, with mass transit and car shares off site, but nearby. That's the exact formula that a developer called Culdesac in Tempe, AZ, is following. This would give people access to the transportation they need when they need it.

Now, of course, a bike path would need to admit larger vehicles at prearranged times for maintenance and moving people in and out. These should be designed to work with the loop transit infrastructure.

Notice also that I didn't factor out the trees. I actually increased their number on a smaller footprint, but in this case, I would still follow a factoring strategy of reducing repetition. This is a sharp departure from many suburbs, which landscape every yard with the same obnoxious, fast growing trees. A few decades later, silver maples, for example, start dropping huge branches on driveways and roofs.

This illustrates a design corollary to my fourth observation about factoring: if you must repeat, don't repeat your mistakes!

Instead of silver maples, I would plant as diverse a forest as possible with plentiful native species. I would select some of these to fix nitrogen and provide leaf mulch to the fruit trees planted among them, and I would locate them in places where that mulch isn't a problem and you don't need to rake.

▲ Step 3: Count your money!

Let's tally the overall value created for the builder and the residents.

▲ Better Amenities

Let's start with the amenities. First the obvious: The factored property has a resort quality swimming pool big enough to swim laps, not to splash around. It has an on-site gym much better equipped than most garage gyms. It has a ground floor cafe where you can hang out with your neighbors and get meals without having to shop and cook. It has a wooded park large enough for lots of people to play, exercise and relax. The plantings of edible fruits, berries and greens encourage people to get outside and explore through the spring, summer and fall. The rooftop greenhouse supplies the cafe with fresh picked produce throughout the year. Bigger windows with better views also brighten the interiors, and there's much less noise and pollution from cars and parking. There's no annoying car alarms, no revving engines, no exhaust fumes.

▲ Better Economics

Let's look at the economics. Well first of all, there's five times less land to buy per resident. Construction costs are 30% less because the apartments share various combinations of walls, roofs and floors. Going multi story does require stronger materials, and fire safety devices, such a sprinklers, add some costs. But these are offset by the much shorter utility runs.

Insulation costs 90% less because of the lower surface area per resident. Heating and cooling is 300% more efficient due to the lower surface area to volume ratio. Combining these factors with the moderating effect of the rooftop greenhouse can easily cut the construction and energy costs of climate control by more than 90%. That gives us a lot of extra budget to invest in high efficiency heating and cooling, such as heat pumps and geothermal.

The roads in this development cost 19 times less because there's four times fewer streets. Twice as many people in the three meter wide bike lane can provide twice the level of service as an eight meter wide street plus sidewalks. There's other savings as well, having to do with the lighter road base needed to support foot versus automotive traffic, and I would invest some of these savings in a roof over the bike paths to make commuting safe and comfortable year round. These would also in turn, reduce the weathering of the road. Transportation by bike costs 20 times less for residents than owning a car. Plus with a bike, you can get your license at age six!

Less hard surface means much less concrete to pour for the storm drains. The gym and greenhouse-to-table cafe are potential profit centers, providing the community with income and on-site jobs.

The wooded park satisfies a deep daily need for wilderness that is proven to boost people's mood—and property values. The higher density makes nearby bus, trolley or other transit systems economically viable. Of course, I prefer Loop transit, as I mentioned in Episode 8.

The total cost to build, own or rent will vary by region, depending on the prices of land and materials. Builders could save 50% or more on overall construction costs, and residents could save so much on transportation, tax, insurance and utilities that their total monthly expenses could fall by 50%, even if they pay a lot more per square foot to be closer to an urban center.

Bottom line: Factoring our design allows builders to substantially increase their profit margins and residents to substantially cut their costs.

▲ Safer and Healthier

This development is also safer and healthier. Children don't have to cross busy streets to visit neighbors in the building. Far more opportunities exist for face to face interaction, so no one remains a stranger for long. Good design—such as clustering small groups of apartments around lounges, libraries or other common areas—would maximize this opportunity to build social capital.

The green space could be landscaped to buffer floods and droughts and planted with fire resistant species. This is easier to implement and manage on a single property than to enforce over time among many separate houses and owners.

There's far less air and water pollution from cars and power plants. And as we saw in Episode 4 and 6, this has really huge implications for our health and for our wealth. Bike commuting provides great health benefits. Because it's more compact, we can build the factored property closer to urban centers, shrinking the commute times. This can drastically increase how much family time the residents enjoy.

Now pay close attention to that last item. Most Americans think of suburbs as safer and healthier than apartments, especially for children. But in his book Happy City, Charles Montgomery has chronicled the exact opposite: bedroom communities with long commutes can become places with no family time at all. Predictably, children end up neglected and alienated: the perfect recipe for gangs, drugs and teen pregnancy.

▲ How factoring reduces stress

Factoring can reduce stress. Now I realize that many people will think of apartments as a big step down from the suburbs. They worry about noise and crowding. My numbers assumed that the apartments provide the same area per resident as the attached homes, and that the common spaces are large, so they won't feel crowded. I've lived in many apartments over the years, and the noise depends on build quality and location. Building with no immediate provision for cars eliminates most of the street noise, so let's assume good acoustic design and follow a suburbanite's move to a property that uses a heavily factored design. He may grumble about it at first, but a year later he has a jolting visit with his doctor. She says, "What happened to you?"

"What do you mean?"

"Okay, here's your chart. Since last year, you lost 15 pounds. Your blood work and vital signs look a lot better. What changed?"

Oh, just a few things. Now he:

- Commutes by bicycle, which builds exercise into his day.

- Has time for daily walks with his kids in the forest.

- Dines with family and neighbors in a garden-fresh cafe.

- Worries a lot less about crime and family drama.

▲ Yeah, but will people buy it?

I've obviously designed this property to be really green. It uses a small fraction of the material and energy required to build and maintain a suburb. It also offers vastly more opportunities to interact with people as well as gardens and wildlife.

Now let's face it, that sounds pretty hippie.

The problem is, in America, hippie sounds downmarket, probably because the counterculture and the back to the land movement were all about renouncing materialism.

Well, today green is gold. I discovered that firsthand when my neighborhood's green reputation propped up my home's value during the housing crash of 2008. And I've confirmed it through additional research and travel, which I'll discuss here soon.

The bottom line is that a housing project that uses factored design will cost the developer much less to build and command a much higher price per square foot than traditional detached housing. For the buyer or tenant, it offers a much higher quality of life than a suburb, at substantially lower monthly cost.

And that's just the tip of the iceberg. As part of a larger development such as Edenicity, this project would present many additional opportunities to factor the design of energy, food, retail, transportation, entertainment and numerous other systems. Each factor would expand a developer's ability to offer better living experiences at higher profit margins with less harm to the earth. This is how it's not only possible to cut our consumption, energy and land use by 95% or more, but how it would offer incredible quality of life.

Last night I went for a walk in a forested park in the city, but the noise from traffic hundreds of meters away drowned out the song of the robins.

I can't wait to build something better, where the cars lose and the birds and the trees and the bicycles win—and so do we.

All we need are some design tricks we learned in grade school, and the courage to actually use them.

▲ Close [music]

If you enjoyed Episode 9, please be sure to subscribe so you don't miss a show. And please join me next time when I'll explain how to make our urban deserts greener and richer by massively expanding the commons.

I'm Kev Polk and this has been edenicity.